The year was 1986 and the Conservative government gave the go ahead for the Channel Tunnel, linking Britain with France, to be built. If it would soon be possible to drive between Britain and Continental Europe, a vehicle could then be driven from London to the most eastern point of the Russian mainland. Now, if it was also possible to drive across the sea-ice between Russia and Alaska, it might then be feasible to drive all the way from London to New York!

Led by renowned British explorer, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the ‘Land Rover Global Expedition’ was born.

Expedition Details

The idea for this expedition was registered with the Royal Geographic Society in London, but this meant that others were in a position to read about the team’s plans. One such person was Richard Creasey who very quickly mounted an attempt to lead the first team to drive all the way from London to New York via the Bering Strait. Using a combination of Ford Maverick and Mondeos, supported by vast Russian Ural 6×6 trucks, the team set out on the 27th December 1993.

In order to cross the Strait itself, a prototype tracked vehicle called an Arktos was used, designed to rescue oilrig crews operating in Arctic waters. Looking like two First World War tanks stuck together and weighing in at 10-tons, the Arktos was flown in from Alaska, to a suitable point in which to make the crossing. Within just 7 hours of leaving the Uelen on the Russian mainland, one of the 2-ton tracks fell off the machine, which took a whole day to refit. At no more than a crawling pace, this northbound journey took days to complete, where upon they suffered a punctured hull on jagged rocks. This was repaired but after no more than a mile or so, even worse was yet to follow - the hull was punctured again, this time by thick ice and they started taking on water. Eventually the order was given to abandon the machine and a helicopter flew out to recover them.

In 1996, the Fiat motor company using 13-ton Iveco trucks, set out from Milan to achieve what Ford had not. They too made it to the edge of the Bering Strait, but opted to turn back as soon as they saw the extreme conditions that they would have to encounter.

By late 1995, Sir Ranulph Fiennes had joined the partnership of Canadian adventurer Dr Gordon Thomas, and Russia’s premier explorer Dmitri Shparo. With such a reputable team, Land Rover were approached for sponsorship. They agreed to provide 3 Defender 110’s and 3 mechanics as team members for the ‘Transglobal Expedition’. They also agreed to underwrite the cost for building a prototype amphibious unit that would be used for negotiating the various bodies of water the team would encounter en route. This amphibious unit was essentially a Kevlar made catamaran, equipped with a hydraulic pump that drove 2 stern-mounted paddle wheels. With the vehicle mounted on top, the pump was driven from the rear power take-off on the Defender. The speed and direction of rotation of each paddle wheel could be individually controlled from within the vehicle to permit steering in water. Eventually, the catamaran was dubbed an LRPC (Land Rover Powered Catamaran).

Although an advert had been circulated within Land Rover asking for volunteers, only 2 men applied for the job of team mechanics for this epic journey - Charles Whittacker and Granville Balis. Ran Fiennes therefore placed further adverts with the Royal Geographic Society and Scientific Exploration Society looking for a third team member to accompany the two Land Rover mechanics - this is where Mac (of Max Adventure) first got involved with the project. Having attended a selection weekend in Snowdonia, run by Olly Shepard of ‘Transglobe Expedition’ fame (led by Ran Fiennes, they were the first team to circumnavigate the earth along its Polar axis using surface travel only), Steve Signal was chosen as the third mechanic. As a former New Zealand Army vehicle technician, he was used to Land Rovers and therefore skilled enough to work alongside the two Land Rover guys.

Mac was chosen as the Arctic Base Leader for our forthcoming reconnaissance mission to Wales, Alaska, but this soon grew to incorporate other roles of Forward Reconnaissance Advisor and Logistics Co-ordinator.

By September 1996 the LRPC was completed and the first tests were conducted the following month at the Royal Marine Training Centre in Instow, North Devon. Instow faces the protected Barnstable Bay where water currents and waves are benign. The tests were useful in that the team established that they could easily and successfully turn the assembled LRPC in water. The reason behind the paddle steamer blades was that they could deal with any dark ‘Bergy’ ice that lies hidden just beneath the surface of the water and can chew a propeller blade up within seconds. A paddle wheel would be able to ride up and over such ice, preventing damage. Some on the spot design changes were made that permitted the craft to achieve a speed of 6 knots at an engine speed of 1500 rpm. Because of pump limitations however, we were not able to exceed the 1500-rpm limit.

Following the tests, Land Rover decided to sponsor the entire expedition and use it as the premier event to celebrate their 50th anniversary in 1998. Accordingly, the expedition was renamed the ‘Land Rover Global Expedition’.

At the end of February 1997, Mac flew out to Wales, Alaska, one week ahead of the main party to set up Base Camp and establish communications. Their Base Camp was an empty vehicle garage belonging to Dan Richard, an American who had lived in Wales since being based at the nearby military early-warning station during his US Air Force days. With no kitchen, hot water, toilets or washing facilities, Mac set about making good as best he could. Much of the garage was full of snow, which would find its way through the tiniest gap in the doorways. With nothing to stop the wind for thousands of miles to both the north and south, it is one of the windiest places on the earth.

A week later, the two Land Rover Defenders, one a military ‘Wolf’ version, the LRPC and all their other spares and provisions were flown out to Wales in a chartered C-130 Hercules transport aircraft. The equipment’s journey had taken it from the UK to Seattle by ship and then by truck to Anchorage before being loaded onto the aircraft.

The team soon settled into their new surroundings that would be their home for the next 10 weeks. While the 3 mechanics set about testing the vehicles in the extreme conditions, Mac made the Base Camp as comfortable as he possibly could, utilising anything that came to hand.

Once established, they set about building the LRPC, which came in kit form like a giant Meccano set. Soon after, both Gordon and Ran joined the rest of the team - they were now ready to test the feasibility of this whole project.

Their intended mission in Alaska was to drive the round trip from Wales to Barrow, Alaska’s most northerly point, with the Defenders. In addition, they planned to launch the LRPC in the Bering Strait to determine its capabilities To accommodate the journey over tundra, the Land Rovers were equipped with Mattracks.

Each wheel was replaced by a single rubber track so that conventional steering could take place. The system consisted of a driving cog that bolted onto the standard hub, with small ‘jockey’ wheels along the base, so allowing the brakes and suspension to work as normal. To prevent the track turning into a ‘triangular’ wheel, a torsion bar was fitted which had to be exceptionally short on the front hubs.

They quickly discovered many design flaws in the Mattracks during early exercises outside of Wales, with the torsion bars being put under tremendous load and the ‘jockey’ wheels breaking off on a regular basis. One of the main problems was that as the Land Rovers lacked locking axle differentials, they would frequently get stuck in the soft snow.

The extra height due to the tracks, along with their heavy loads, meant that they would lean over more readily, causing the two high-sided wheels to break traction. With the extreme cold they encountered and therefore the problem associated with batteries, it was decided to fit mechanical winches equipped with ‘shear bolts’ to prevent overloading. Unfortunately these bolts broke on a regular basis causing them problems with self-recovery.

However, the team successfully travelled from Wales to Teller and back, which was the first time motorised vehicles had done so in the winter. This required negotiating a relatively high, snow-choked pass in the York Mountains. This was largely accomplished by repeated digging with the winches pulling on a buried deadman in the frozen crust.

The frequent failures of the Mattracks (which were repaired with welding gear in their Base Camp) and the persistent need to dig out the Land Rovers caused them to scratch their plans to travel to Barrow. Between the six of them, they then hatched a new plan that would get them to the road system near Fairbanks.

The Bering Strait would now be crossed during mid-June (or earlier if all the ice had gone). For this purpose, the LRPC would be flown by transport aircraft from Anchorage to Lavrentija, Russia and brought by a Russian military vehicle to Naukan, an abandoned Eskimo village south of Uelen.

Arrangement were made to be met in Naukan by experienced natives from Inalik, Little Diomede. They ply the waters on a regular basis in pursuit of their fishing interests and agreed to guide the team across to Wales, Alaska. From there, they would travel by water to Teller and then by road to Nome while the LRPCs were carried by truck.

Launching the LRPCs back into the water at Nome the team would then hug the coastline of Norton Sound until they come to Kotlik where a tributary permits them to enter the mouth of the Yukon. This entire area was the object of intensive investigation by Ran, Gordon and Steve during their Alaska recce, using snowmobiles and a low-flying aircraft. The plan was to then travel on the Yukon, connecting with the Tanana River to the town of Manly Hot Springs. Reaching Manly was anticipated by mid-July. From there, the team could connect with the road to Fairbanks.

The journey across the rest of North America would eventually take the team to Cape Breton Island in the northern part of Nova Scotia, for the journey across the Cabot Straits to Port aux Basques in Newfoundland. The following year, Mac drove 5,000 miles across Canada with Gordon to recce the final crossing to Newfoundland.

The distance across the Cabot Straits is 66 miles, but the Strait of Belle Isle further north, separating Newfoundland with the coast of Labrador, is just 15 miles in length and was considered a safer option. This however would mean driving up the northern shore of the St. Lawrence River until the road ended and then using the LRPCs to hug the sheltered coastline to Blanc Sablon before crossing over to Newfoundland.

At each of the four water crossings - Irish Sea, English Channel, Bering Strait and Strait of Belle Isle, it was planned to have overhead helicopter support in case of emergencies. This was in addition to Lifeboat cover and local guides in their boats to lead the way. All team members were to be equipped with cold-water survival suits and the LRPC to be outfitted with appropriate marine safety devices.

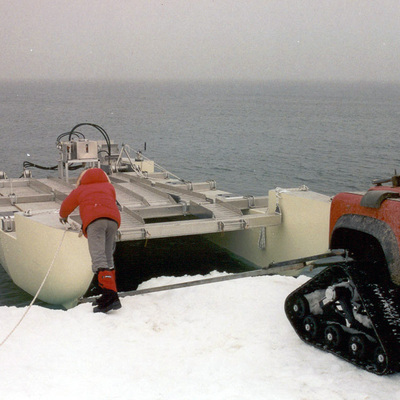

The LRPC weighed 2-tons. At Instow, two American WW2 Ducks launched it, since the Land Rovers lacked the power to pull it across the beach sands. In Alaska though, they discovered that it was an easy matter to assemble it on the ice bordering the Strait and tow the fully loaded 5-ton unit by the other Land Rover. Their major problem was to devise a method to get the LRPC over an 18-foot pressure ridge and into the water.

Charles came up with an ingenious method. He welded an A-frame together, attached it to a Defender and pushed the LRPC straight into the water. Appropriate precautions were taken to keep the Land Rover from being dragged in with the LRPC, using winches and the other vehicle as a deadman.

The rough edges of the pressure ridge were smoothed with the aid of a chain saw, axes and shovels. They practised the launching procedure several times including driving the Land Rover on board until the procedure became routine.

Finally, they embarked on a water cruise of the Bering Strait. The strongest current there is the Wales current (3 knots) near the tip of the Seward Peninsula. They struggled to cross it and endured a greater struggle to return to the launch site. Nevertheless, they concluded that the tests were successful. They felt that the Strait could readily be crossed with a vehicle-powered amphibious unit provided a maximum speed of 8 to 10 knots could be attained. They had proved that the Land Rover Global Expedition was feasible.

After 2 ½ months working in the Alaskan wilderness, the team bid goodbye to Dan and the Inuits who they had become so friendly with and boarded the Hercules for the flight home. Three days later they were back in ‘Blighty’ raring to get started on one of the last great challenges on earth.

The leaders reported their findings to Land Rover at a meeting held in London in June 1997, where the plan for the entire expedition was discussed in its entirety. Unfortunately, the situation within Land Rover changed and the following month the team received messages from them cancelling their sponsorship because of an adverse business climate.

So, the challenge is still open.